Part 4 - A Nation Grows Older: When did Excess Deaths start?

Teasing Temporal Trends from Incomplete Data

Once upon a time, the World Health Organisation1 used to described a pandemic thus:

“An influenza pandemic occurs when a new influenza virus appears against which the human population has no immunity, resulting in several simultaneous epidemics worldwide with enormous numbers of deaths and illness.”

[NOTE: Substack says this post is too long for email, so please click to read the post in full at Witzbold’s Substack]

Swine Flu Swindel

Controversially2 the WHO amended this description on its website by dropping the “enormous numbers of deaths and illness” part shortly before declaring the so-called Swine Flu pandemic in 2009. Highly recommend reading is this English language report from the German magazine, Der Spiegel, to refresh your memory about the heady days (daze?) of public health panic and hysteria back in 2009. Do be warned, it involves an unsettling dosis of dejá vu concerning the pharmaceutical lobby’s vested interests in such times of uncertainty and fear, while the massive government vaccine purchasing agreements concluded are similarly back to the future: “Reconstruction of Mass Hysteria: The Swine Flu Pandemic of 2009”.

Show me the Money Data!

Anyway, the public understanding of a pandemic remains very much so one involving enormous numbers of deaths and illness and so it is a matter of course to examine the mortality trends both during and in the aftermath of an officially declared pandemic, particularly one deemed a once-in-a-generation granny-killer that warranted “locking down” schools, much of social life, and restricting basic civil liberties. Right?

So far our efforts regarding Irish deaths data have revolved around analysis of annual percentage death rates for the various age cohorts. Based on this we have already stated “…there are no signs of an alarmingly deadly pandemic in 2020 in the deaths data for Ireland”. Much of the remaining analysis attempted to quantify the extent of excess deaths in the successive years but remains provisional because of the incompleteness of the publicly available data.

When Exactly did Excess Deaths Increase?

This post will now come at the data from another angle, namely, deaths rates by month in an effort to more narrowly identify and compare mortality trends during different phases of the past four years (2020-2023). As the Irish Central Statistics Office does not (currently) make deaths data available which are broken down by both date of death and age, we will have to wait to conduct a more thorough analysis on that front.

Mortality Seasons

A preferred epidemiological approach to analysing deaths data is to center a so-called mortality year around the season of greatest mortality. For Ireland and other northern European countries, these are the colder, darker winter months. For example, we can use July-June and avoid any possibility of deaths from separate winter seasons, cancelling or amplifying each other in annual deaths totals. Mortality seasons were previously covered in Witzbold’s Newsletter here:

Mortality Years

In order to better consider such mortality seasons we need to split the annual calendar year death totals, and to do this we need deaths totals by month or, at the very least, by quarter. CSO dataset VSD39 provides deaths totals by month. However, as already discussed in this series, Irish deaths data is incomplete due to the late registration of many deaths requiring a coroner’s certificate - see “Late Registered Deaths” in previous article: Part 3 - A Nation Grows Older: Disparate Mortality Trends and Other Demographic Curiosities

Monthly Totals

The first step for the years 2011-2019 was to take the incomplete monthly totals from dataset VSD39 and scale them up by a uniform factor to match the revised yearly totals from VSA35. For example: the 2019 monthly totals add up to 31,184, but the revised annual total is currently 32,101 because over 900 deaths were registered late, i.e. after the CSO’s Vital Statistics Annual Report for 2019 released which was released in 2021. Therefore multiplying by (32,101/31,184) scales the monthly totals to sum to the revised calendar year total.

Coroner Backlogs

We do not yet know the final totals for 2020-2023 because of the afore-mentioned pending late death registrations - and which may not be an insignificant amount due to the increased number of coroner’s certificates requested during the pandemic and the reported growing backlog being experienced in Ireland’s coroner’s offices: Dublin's coroners express 'grave concern' over backlog of inquests due to staff shortages.

Ad Hoc and Experimental Analysis

However, the CSO undertook a commendable analysis during the pandemic to investigate using public data in the form of online death notices to offer a more immediate measure of mortality trends: Measuring Mortality Using Public Data Sources 2019-2023 (October 2019 - June 2023)3

Deaths that are referred to the Coroner’s Court may also take years to be reflected in official statistics due to the length of time to complete the court process. Given the need for more timely data as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the CSO began to explore experimental ways of obtaining up-to-date mortality data.

Death Notices vs Death Registrations

One section of the publication explicitly explores coherence between counts of death notices and officially registered deaths by date of occurrence for the period Quarter 1 2020 to the end of Quarter 2 2023 [our emphasis]:

As we look further back in time and as more deaths are registered officially, the gap closes between the two sources. Data for Q2 2022, one year prior to the study, is broadly equal for the two sources. However, from approximately Q1 2021, over two years after some deaths occurred, there is a slight divergence between the two sources and officially registered deaths are in the region of 3 to 5% above the number of death notices. As it is unlikely that every single death has a death notice posted it would be expected that the official figures should eventually be higher than the number of death notices.

Ad Hoc Monthly Totals

For the years 2022-2023 the CSO does not provide any monthly or quarterly totals of deaths by date of occurrence, and for 2020-21 it provides only incomplete totals by month as per the annual reports (available in VSA07). However, as part of the experimental analysis of the public death notices, the CSO has made the following datasets available: RIP04 and RIP05 offering cleaned counts of monthly death notices for the periods 2021-2023(up to June) and 2020-2023(up to June) respectively.

For the purposes of this analysis we have scaled the quarterly totals from dataset RIP05 by 1.04 (splitting the difference of 3~5% cited by the CSO publication). As a further point of reference and justification for this approach, the revised Q1 2020 (non-pandemic) deaths total is currently 4.4% greater than the cleaned count of death notices for the same period and the revised 2020 year total of 33,218 is currently 3.9% greater than the cleaned count of death notices for the same period. Using the scaled calendar-year totals we can again similarly scale the available monthly totals to match the hypothetical (104%) yearly totals of 2020-2023.

All indications currently suggest registered deaths for 2020 will eventually surpass 104% of the cleaned death notices for 2020. We see no obvious reason why the ratio of registered deaths to death notices should decline for succeeding years. Indeed, both CSO and HIQA refer to increasing coverage and reach of RIP.ie in recent years. Therefore we consider our estimates to be more likely a hard floor and subject to upward revision as the data becomes more complete.

[EDIT: i.e our estimated values should be considered minimum values]

Crude Population Adjustment

The final step is to perform a crude population adjustment (recall we do not yet have monthly data by narrower banded age groups) and divide by total population size before regrouping the calculated monthly death rates into mortality years of July-June, i.e. these are overall crude monthly death rates per 1,000 population. [Note: CSO provided population estimates are for April, nevertheless, I have used the population estimates from the same calendar year for Q3 and Q4 and the next calendar year for Q1 and Q2 of each mortality year.] Voila!

Spot the once-in-a-lifetime Pandemic

Let’s play, “spot the once-in-a-lifetime pandemic”, again! Remember these are crude rates per 1,000 population, [EDIT: and so are directly comparable with previous years., - they are not yet age-standardised, meaning population structure is not taken into account.]

Well, there are a number of individual months with very high death rates: January 2017, 2018, and 2023, admittedly 2021 is the highest. Then there is an April which clearly stands out in 2020 (albeit following milder December/January rates in comparison to 2013/14 through 2017/18). And there is winter 2022/23 which saw back to back months December-January of markedly elevated monthly death rates. Oh, and there is a winter season 2021/22 which saw four successive months of death rates above 0.6 per 1,000 population more than any other mortality year in the period examined. Finally, the summers of 2021, 2022, and 2023 all exhibit rates elevated above all previous years. [EDIT: “baseline” depicted simply to emphasise contrast across summer months]

Total Population Trend

Regular readers will be aware of the issues with overall population crude death rates - the disproportionate distribution of deaths within a population can hide disparate trends in sub-groups such as smaller age cohorts (Simpson’s Paradox). With that disclaimer in mind, note how the plotted line above the monthly bars reveals mortality years 2019/20 and 2020/2021 were marginally above the linear trend line (at 6.71 and 6.64) which had been extremely stable 6.35~6.65 deaths per 1,000 population per year prior to the pandemic. Observing that the two mortality years which deviate most from this trend are 2021/22 and 2022/23 (at 6.97 and 7.10), we would assume the pandemic must lie there. Did we get it right?

Data Visualisation

Unfortunately, after spring 2021 the Irish Central Statistics Office appear to have stopped producing the above type of diagramme in their publications on excess death. Note how tight the band of crude mortality rates are for July-December over the years - except for 2021/22 and 2022/23. Note, also, how high previous winter peaks were, their shape, and when they occurred (January). Finally secondary minor peaks were common in March. Remember, these are crudely population adjusted and [EDIT: thus directly comparable.- they are not age-standardised, meaning population structure is not yet taken into account.]

Let’s now highlight the pandemic years:

2019/20

A relatively mild winter followed by a strong peak in late winter - abnormally in April. Here we can recognise the danger of neglecting the broader seasonal picture: although the April peak’s timing is abnormal, its magnitude is broadly similar to previous winter peaks, for example, winters 2016/17 and 2017/18. It should also be noted from the first barchart that the prior winter season was markedly low, meaning a return to mean (if not, slightly above mean) could reasonably be expected for 2019/20. Taken as a whole, 2019/20 was marginally high.

2020/21

Exhibiting a very strong mid-winter (January, and unusually February) peak, but otherwise an unremarkable year. There are even indications of less than normal death rates thereafter in spring 2021. The overall magnitude is even a little less than 2019/20, perhaps a sign of returning to mean. Taken as a whole, the 2020/21 crude rate appears to be in the normal expected range.

Post-Vaccination

Now let’s highlight the post-vaccine years:

2021/22

Lacking a clearly defined winter peak, but with remarkably elevated crude rate from July to December and also April onward. “Flatten (and elevate) the curve”, anyone?

2022/23

Exhibiting a strong early winter (December-January) peak, it also retains the markedly elevated death rates in almost every month over the 12-month mortality year.

[EDIT: Recall, our estimated values for 2021-2023 should be considered as minimum, they will almost certainly climb higher]

Ireland’s post vaccination mortality trend echoes observations discussed in a previous post, “Excess Deaths: The Slow Burn” highlighting England’s data:

Waves that crash - Waves that keep rolling

The initial Covid-19 waves are clearly recognisable as waves: they rose, crested, and fell again to negligible levels. Yet in England 2021, in the middle of summer, cases unseasonally shot up again to winter levels! The MSM repeatedly attempted to assuage any concern by assuring us that hospitalisations and Covid deaths were NOT climbing correspondingly as they had in the previous waves and that this proved vaccine effectiveness. Perhaps, but what has horrified me most is that all-cause deaths did climb above normal levels and have thereafter not subsided - the new normal?

It could also be likened to a forest fire: the first waves raged furiously, burning through all dry wood available but ultimately exhausted themselves (I do not accept lockdowns or other non-pharmaceutical interventions played any significant role in extinguishing the forest fire curves). However, since summer 2021, a low level burn has persisted. It did not spike (until last month) and thus failed to trigger screaming MSM panic levels but neither has it subsided to normal pre-pandemic levels. It just keeps burning. Has the baseline level of mortality been raised?

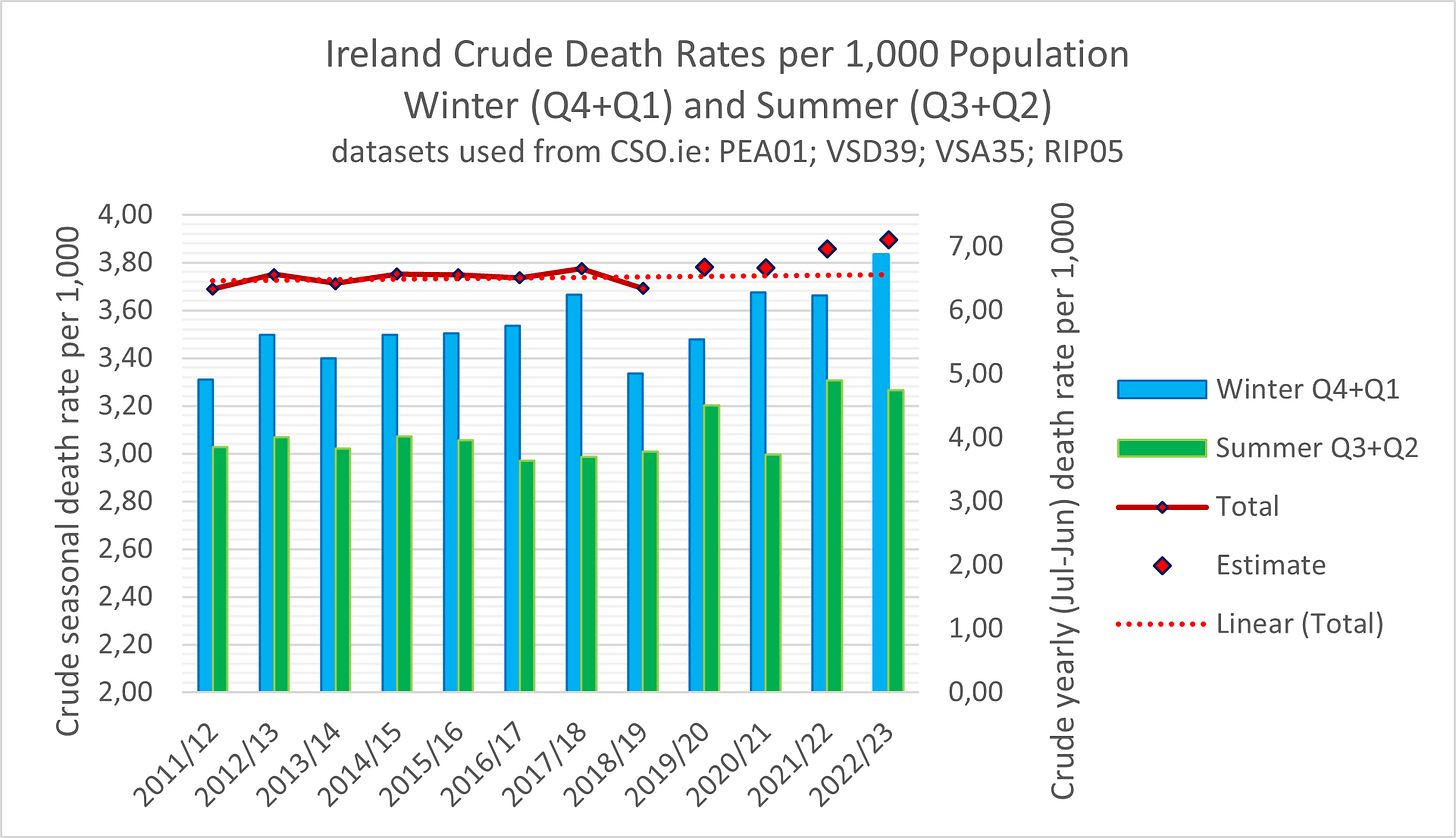

Quarterly Visualisation

Finally, because there is no rule that individual monthly/weekly/daily totals should follow a particular temporal pattern (although they often do), we can group by quarter to average-out slight variations and some of the outlier months to get a broader overview of overall deviations from the pre-pandemic averages but still more detailed than annual totals.

The barchart below emphasises that the Q1’s have been relatively normal in 2021/22-2022/23 but it is the Q3, Q4, and Q2 which are all markedly above average.

Combining Q4+Q1 reveals winters 20/21, 20/22, and 22/23 are all above the pre-pandemic average and similar to the previously highest winter rate in 2017/18 (winter 22/23 is the worst in our period). Notably, the summers Q3+Q2 are equally contributing to the slow burn effect which has pushed the post-vaccine mortality years (July-June) into excess deaths territory.

Conclusion

Ireland has been experiencing statistically significant excess deaths, when mortality years (July-June) or quarters are considered, this mortality trend is observable since July 2021 [EDIT: as our figures since 2021 are minimum estimates, the extent of excess deaths will be greater when data is complete]. Importantly, there has been no expected reversion to mean after the slight increase during the pandemic period prior to the vaccination campaign, instead the overall crude death rate has counter-intuitively continued to climb. Also, the temporal shape of the mortality year in Ireland seems to have significantly changed/shifted. Will it revert to normal patterns of winter peaks in January and lower summer levels, or will the slow burn continue?

Next up will be to (hopefully) get monthly deaths data by age group, so we can examine not just when, but additionally to whom, the excess deaths have been falling on a monthly basis. Only then will it be instructive to examine the vaccination campaign data for any correlations. (Ireland has very detailed publicly available information about its vaccination campaigns.)

As ever, any comments, criticism, and feedback are very welcome!

Part 5: What goes up, Must come down?

Why haven’t death rates fallen, or have they? As ever, the key is to gauge expected mortality rates based on both previous years and population dynamics like size, age, sex, etc. While true that annual death totals in Ireland have not continued to climb after 2022, it also appears they have not fallen back below trend (so-called deficit deaths) to balan…

Pandemic preparedness [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003 Feb 2. Available from: http://web.archive.org/web/20030202145905/http://www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/pandemic/en/

“The elusive definition of pandemic influenza”, by Peter Doshi https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3127275/#R6