[UPDATED] Part 2 - A Nation Grows Older: % Mortality Rates and Other Demographic Curiosities

- an Irishman dons his hobby statistician's cap

==UPDATE 29.11.2023==

Due to using a dataset in the original Part 2 post which was not updated, and in light of important criticism from a reader in Ireland, this article is being re-published with an updated dataset for years 2011-2020, corrected charts, and some background information on the peculiarities of the Irish death registration process.

====

The Rep. of Ireland experienced its highest number of recorded deaths in 2022 since the 1950’s. Many citizens, and politicians have expressed concern about the high number of deaths.1 This series attempts to to better understand if there is excess mortality, to quantify it, and to locate it in the Irish population structure by using publicly available data from the Irish Central Statistics office. Part one is here:

Continued…

Recap

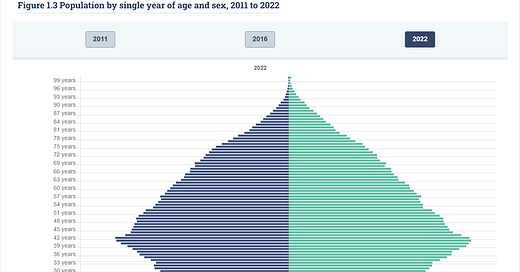

Recall Part 1 showed the population of Ireland has recently been experiencing increased annual deaths totals. It also showed Ireland has experienced rapid demographic change with the size of its elderly portion of the population (70 and over) growing 28% between the census years 2016 and 2022. How do we disentangle these two trends in order to quantify the extent of any excess deaths? One suitable approach is look at % death rates by age group.

Pandemic % Mortality Rates in Ireland

Using percentage death rates makes comparability across years more meaningful because % mortality rates for a particular cohort should not be affected by changes in the population size of that age group. This is important, because the Irish population structure is not uniform and the elderly population is growing (as we saw in part one of this series). This means we DO expect total deaths to increase but we DO NOT necessarily expect % mortality rates to increase - “not necessarily”, because there can be overall health and life expectancy differences between generations, for example: today’s 80-84 cohort were born 1939-1943 during WWII and might (on average) be more or less healthy than those from five years previous (born 1934-1938 pre-WWII).

The following graphic displays two tables: the death totals (above) and the % death rates (below) per calendar year by age group, i.e. the upper table shows the total number of deaths in each age group in a given calendar year and the lower table shows the percentage of each age group that died in that year. Rows representing age groups are colour-ranked by year: white is lowest value, red is highest.

==A comment from Irish reader, and fellow substacker

(who has been doing a lot of research on Irish excess deaths) led to learning the CSO’s 2021 and 2022 deaths totals from their annual reports are still provisional and a sizeable upward correction in the range of ~1300 for 2021, and ~1800 for 2022 can be expected. Therefore, the 2021 and 2022 figures in the tables below are to be considered absolute minimum values! With that in mind, let us (re-)examine the mortality trends in Ireland.==

Wow! The table of death rates paints a very different picture to the table of death totals! The first thing that jumps out is that the years in which death rates were clearly severest for almost every age group were 2011 and 2012. Where were the alarmist government warnings or media fear-mongering in those years? Secondly, and similar to the German bean counter’s finding, the updated Irish deaths data for 2020 does not support claims of an alarmingly deadly pandemic. In the context of the 12 year period depicted, 2020 was percentage-wise quite a mild year for all age groups except the 30-44 ages.

Counter-intuitively, 2011 shows the lowest overall % mortality rate and 2021-2022 already appear as the top years for the overall % mortality rate in the lower table, but this is a type of Simpson’s Paradox and has a simple explanation. Consider 2011 and 2012, where we see higher % death rates for almost every single age cohort than in 2021, yet, somehow, 2021 has a higher overall % death rate - how can this be? It is because the population structure has changed and there is a significantly greater proportion of elderly in 2021. So although the % mortality rates in the older age groups are lower in 2021, those groups represent a larger portion of the overall population and consequently a higher overall % mortality rate and higher total deaths is the result.

Because data tables (even those with nice colour-ranked rows) are not everybody’s cup of tea, here are the same deaths totals plotted for the 40+ age groups to better visualise the mortality trends over the period 2011-2022 (shading indicates the pandemic years 2020-2022):

Once in a Generation Pandemic?

Can you recognise 2020 from the charts as the year of a once in generation pandemic? Notice any spikes in elderly death rates? Nope, we clearly see deaths totals rose or continued to rise in the elderly cohorts (left and middle images) in the first year of the pandemic: 85+ age group but not remarkably so; 80-84 an uptick after three years of stability; 75-79 saw a marked uptick through the pandemic after three years of stability; 70-74 nothing unusual, likewise 65-69 and 60-64. Right image: deaths fell in the 65-69 group; otherwise nothing of note.

More importantly, examine the same age groups, but this time showing the percentage death rates (which removes the effect of increasing population size):

Again, where is the pandemic in the official data? We were told the SARS-Cov-2 corona virus hit the elderly hardest so it is surprising to see that in the charts showing the mortality rates of the older age groups (left, and middle) there are also no dramatic increases to be seen - admittedly a slight uptick in the over 80s and 70-74, though ostensibly within the bounds of normality for the 12-year period plotted. None of the % death rates in 2020 stick out as remarkable for the period considered.

As already mentioned, 2021 and 2022 are subject to upward revisions so it is limited what we can say at this point but none of the provisional values (marked with ‘x’) immediately suggest dramatic increases (with the exception of 55-59 age group in 2021).

Here are the younger age cohorts for comparison:

(upper images - deaths totals; lower images - percentage death rates)

Once again, 2020 shows no unusual increases, except the 35-59 age group which saw increases in excess of the immediately previous years (albeit a similar % death rate to 2011-2012). The under 1’s age group also saw an increased death (albeit within the range of values for prior years). In contrast, the 20-24 and 25-29 cohorts saw notable decreases in their % death rates. The ages 1- 19 also saw no unusual changes.

Note: The younger age cohorts are likely to be more affected by the 2021 and 2022 figures being subject to upward revisions. This is because there are fewer deaths in those groups and therefore even small increases can significantly affect the calculated mortality rates per age group. In addition, the younger cohorts are historically disproportionately subject to late registered deaths pending coroner’s certificates (see Part 3).

Apples and Oranges

A further analysis can be applied using the calculated mortality rates to improve comparability between different years for the same population when assessing which is a “excessive” year, or not. We can calculate the expected deaths for any given year using the mortality rates of another, for example what would deaths in the 2020 population have looked like if the mortality rates of 2011 had applied2.

Applying the mortality rates of previous years to the pandemic years 2020 shows how decisive the base reference mortality rates are. Below are tables of the mortality differences between the actual or provisional death totals and the hypothetical death totals for 2020 based on mortality rates from prior years:

The final two rows show the modelled difference as a total and percentage, green hues indicate deficit deaths (less than expected) and red hues indicate excess deaths. The pink highlighted values in the upper horizontal rows of the age cohorts represent excess deaths according to the mortality rates used, green represent deficit deaths.

1st Model

Modelling hypothetical deaths for the first year of the pandemic (2020) by applying mortality rates from previous years suggest it was only a year of excess deaths if judged by the mild 2019 mortality rates. All other mortality rates from the previous years suggest 2020 (the year of a once-in-a-generation deadly pandemic) was a year of deficit deaths (i.e. less than the hypothetically expected mortality). Notably there seems to be large agreement in the mortality rates that there was excess deaths in the 30-44 cohorts (approximately 10% when compared to 2017-2019). This may indicate so-called “deaths of despair” associated with lockdowns and other pandemic measures in 2020.

Significantly, the modelled expected deaths show deficit deaths shrinking as more recent mortality rates are applied.

Trend: Declining Mortality Rates

Thus, yet another trend has revealed itself (visible also in the plotted percentage death rates): although Irish death totals were rising (or steady) across the various age groups in the pre-pandemic years, the percentage death rates were actually sinking. This indicates improved health (or health care) and life expectancy.

In order to accurately determine excess deaths, we need accurate estimates of expected deaths and additionally incorporating pre-existing trends can offer further improved accuracy in modelling expected deaths (on top of our adjusting for population growth and aging population).

Recall how we criticised Eurostat and Euromo in Part 1 for ignoring the upward trend in Irish deaths totals and population size resulting in overestimated excess deaths? If we were to ignore the downward trend in % death rates, we would be guilty of underestimating excess deaths. This significant aspect will be explored in the third part of this series attempting to identify, quantify, and locate excess mortality in the official Irish deaths data.

Part 3 follows:

Hypothetical Deaths = %_Death_Rate(Prior_Year) * Population_size(Target_Year)

Modelled_Difference = Actual_Deaths(Target_Year) - Hypothetical_Deaths(Target_Year)

%_Difference = Modelled_Difference ÷ Actual_Deaths

Here the original comments from the first version of this post:

==

From: Patrick E Walsh

Hi,

you have used INCORRECT figures for 2022 in your article. You have used REGISTERED deaths IN 2022 while all other years are ACTUAL deaths.

The actual figures for 2022 will not be released until October 2024 which I highlighted in an article of mine ‘Excess Deaths in Ireland Age is no barrier’, that you read and commented on.

I also replied to your query as to where I got the figures saying ‘its important to remember that there is a difference between the Annual Report and the Yearly Summary’.

When the 2022 ACTUAL figures are released in Oct 2024 I have no doubt they will be much higher eg there were 33055 deaths regd in 2021 but the Actual deaths per CSO was 34844 as you used. Thats nearly 1800 extra !

I have broken my own rule as regards not critiqueing other peoples work unless asked because considering our previous correspondence I do not doubt your intentions in these matters.

I will not comment or engage again on this but you might consider the appropriateness of using Census 2022 pop analysis where hundreds of thousands of permanent irish people under 40 have emigrated over the last few years to be replaced by in many cases temporary immigrants whose deaths would never be registered in Ireland.

There is also an increased backlog of inquests for deaths in under 40s that I wrote about which means their deaths cant be registered eg 2 high profile inquests for young men who died duddenly in 2021 (T McGinty & R Butler) will not be in the figures. These are statistically important points as there are so few deaths in these age groups. There is also cause of deaths to be considered.